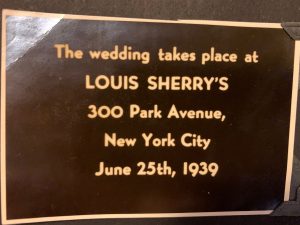

When Dad and Arlene sailed on the S.S. Santa Elena between New York and the Bahamas in 1939, Nancy was not yet born. Ned had married Arlene five days before at Louis Sherry’s , 300 Park Ave., in New York City. It was a fancy and elegant wedding, in an ostentatious setting.

A ship log miraculously excavated by our yahoo angel, lists the two passengers, one 28 years old, the other 19, with the same last name, Schwartz. Schwartz was Dad’s last name before he changed it to Shaw.

Only quite recently has a family member told us that he knew of, and even had in his possession, Ned and Arlene’s wedding album from 1939! Little is known about the wedding, including who the guests were. But I was excited and wanted to see it immediately. It took a while to find it’s way to me, but the damage had long been done. The paper pages are disintegrating, freeing most of the photos to clump in the creases, no doubt allowing some to be lost and with them any intended order. But most frustrating is the fact that very few of the people in the photos are recognizable, at least to me and my family, except for Ned and Arlene. The mother of the cousin who found them in his possession was Dad’s sister. We are still not sure of she was even there.

Actually, some sense of chronological order was preserved:

On the boat to Bermuda

Ned’s grandfather, Samuel Schwartz, was a Jewish immigrant from Hungary. The way the narrative was told to the children of my generation, my father, Ned Schwartz, was insecure about launching a fledgling career as a doctor with a name that quickly revealed him to be Jewish. It didn’t help applying to medical school either, and ironically, given the emergent politics of the region, being Jewish led him somehow to choose to attend medical school in Freiburg, Germany. As Bloomgarden writes early in 1953 in the journal Culture and Civilization, the unsuccessful Jewish applicant to medical school in the United States was likely to share with the professional boxer the shock of “not knowing what hit him” when he was rejected. The picture eventually became clear, if also astonishingly bleak.

If I may digress for a moment to share another family narrative related to this one. Dad never finished medical school in Freiburg. I was, by way of “explanation,” told the following. A German girl Ned was seeing began to be harassed by the Nazis for “dating a Jew.” How they found out he was Jewish isn’t clear, since according to the same oral narrative passed down through the generations, Dad listed his religion on German entry forms not as Jewish but as “Pedestrian.” Good one Dad!

When his girlfriend reported to him that she was being harassed, Dad called the local Nazi headquarters and claimed to have information about some secret activities of the Jews in the area. “Meet me at the train station, and I will share what I know,” he told them on the phone. At the agreed upon time, Dad and a friend who was also studying medicine in Freiburg met the German(s) at the station, beat them up on the train platform, and immediately got on the train for Bern, Switzerland, where both of them finished their medical education. Although unchecked for veritas, if stories like these grow in truth in direct proportion to how often they are told, this one would now be truer than true. It’s one of my favorites.

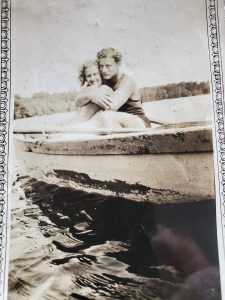

A decidedly untold narrative about Ned, but one that wasn’t altogether unknown to other members of his family, was his proclivity to be drawn blindly into relations with beautiful women. This picture, for example, surfaced with (but not included in!) the wedding album. Others have surfaced from time to time and trace back to who knows where, when, and whom!

All I had ever heard about Arlene while my father was still alive was that she was as “bitchy as she was beautiful.” What I’ve heard in the course of researching Nancy’s life, and not least of all from Nancy herself (in her writing), confirms the bitchy part in spades and well, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Suffice to say Arlene drew men out of the woodwork like honey draws bears out of the forest.

In this post, and perhaps in the next few, I will let Nancy describe, with characteristic humor, irony, and a surprisingly healthy degree of emotional distance, the challenges of growing up under the “care” of an abusive, narcissistic mother whose next act as a parent and as a woman was completely unpredictable.

When I was ten years old, my mother chopped my finger down to the bone with a kitchen spatula.

I don’t know why she did that. I had just walked in the door.

When I was twelve years old, my mother crushed a glass Christmas tree ornament onto the back of my hand because I had placed it on a different branch of the tree than the one which she told me to place it on.

When I was fifteen years old, my mother threw a vase across the room at me, and the pieces shattered on my arm in three places.

When I was an adult, my mother said to me ‘you were never a sunny child.’ (I wanted to say, well, the sun doesn’t shine through scar tissue. But I didn’t.)

Nancy was born in 1942. She describes going to camp in 1952, when she was ten. She would be 74 now.

When I was sent to summer camp for the first time, I was as un-socialized as a feral wolf. It was 1952, and I was ten years old.

That fall, when I came home from public school, I found the owner of the summer camp sitting in my living room with my mother.

This must have been serious, because this man made a trip all the way from another state, in a different season, in different clothes.

My puzzled look must have been apparent, and my mother explained the man’s presence this way: ‘He’s here because you were a terrible camper, and he doesn’t want you back. I’m trying to convince him to take you back.’

Was I supposed to feel grateful? I didn’t know what I had done.

But I said nothing. And she was finished too.

He didn’t say a word to me.

I wanted to be included and informed, if this was about me.

But I was just a scapegoat.

Actually the camp was owned by this man in my living room and his wife, who not only was not in my living room, but didn’t know that her husband was.

My mother sent me upstairs feeling awful.

It was apparently a regular occurrence, discovering her mom with a strange man in the house.

I wondered why the rabbi was in our house.

It didn’t ring true when my mother said she was ‘seeking guidance’ because her children were the children of divorce.

She never sought guidance before and now was no time special.

I thought it was really strange too how the rabbi appointed me the valedictorian of my Sunday school confirmation class. [Nancy seems really confused here about names and titles, and their place in her narrative, and in the rabbi’s faith.] I had only been there that one year, and did not shine or stand out in any way.

I thought maybe since the rabbi kept appearing in our living room, that the fate of her children had so moved the rabbi that my mother’s tales of woe and hardship inspired him to bestow the “flower address” to me, out of pity.

It wasn’t until someone said to me, ‘maybe the rabbi wants to get next to your mother’ that I realized ‘absolutely!’

Now that rang true.

An electrician, a camp owner, a doctor, a businessman……I had no trouble figuring out. But a rabbi? I thought they were supposed to be religious.

Whatever is a “flower address,” I have no clue.

Nancy’s brother, Billy, born to Harold Russek who was next in a long line of suitors and husbands after my father, was crippled emotionally. His status today is unknown. The yahoo “angel” who found Nancy for us (described in The Background Story) managed to contact Billy, but Billy was not open to contact with us, for reasons we can only imagine, but will never truly know.

My mother laughed unmercifully at the misspellings in my brother’s letters. She showed them to everyone, including me, mocking him like a throwaway.

He had been writing home from summer camp in 1954. He was only ten years old.

That fall he proudly told me he was voted ‘the most improved camper.’ I knew how he felt and was so happy for him.

He was dearly trying to be appreciated somewhere.

Billy and Nancy spoke about their mother as little as possible when they were together. When they did, it was tough for Nancy to swallow.

My brother was telling me things and I heard them in delayed reaction. The were about my mother and too despicable to ‘hear’ in real time.

Nancy, in her writing, sometimes pauses to ponder the pain of childhood, and to reflect on how in the world she was able to survive.

I suffered as a child, things no child should have to suffer.

I didn’t deserve it. I had always thought that I did.

Referring to the life she and Billy were forced to lead:

To maneuver as a child through a loveless, dangerous family is like taking your first steps through a mine field.

You have to think about way more than you should.

We did the belly crawl under barbed wire every day of our lives.

Nothing was ever really my life. I could lay claim to nothing. I didn’t know what the war was that was going on above my head.

It didn’t sound like music.